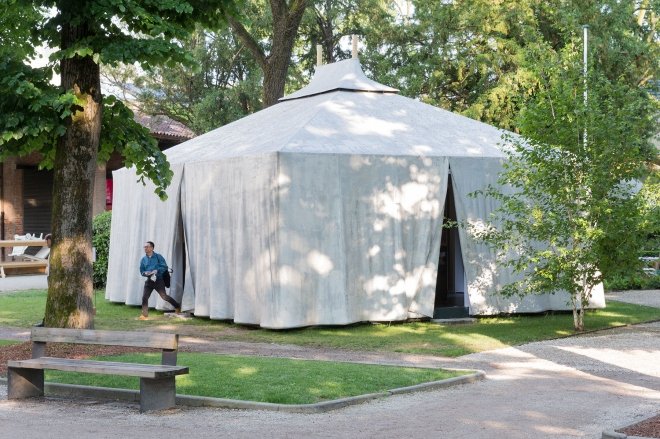

Western Sahara Pavilion

Biennale Architettura di Venezia 2016

Participant: Manuel Herz with the National Union of Sahrawi Women.

Project Team: Fatma Mehdi Hassan, Warda Abdelfatah Mohamed, Chej Mohamed Chadad, François de Font-Réaulx, Penny Alevizou

Weaving: Ajdaija Salak, Jaiduma Balaly, Achaia Daihy, Aichatu Almahyub Damaha, Atfarah Laman, Safia Said, Sukena Dahwar, Wanaha Bala, Salma Daidu, Asania Mohamed Asuelam, Fatma Haimad, Fatimatu Buda, Anaga Gasuani, Alhasina Hasana, Daidu Ambarak, Fatimatu Akrum, Manati Amaigal, Fatimatu Labaihi, Alueha Jatri, Fatma Aljer, Tchla Pachri, Argaya Achaij, Mahyuba Ahmatu, Fatma Ambarak, Atfarah Asalak, Mahyuba Alaal, Angaya Ahmed, Mariam Mohamed, Ajrebicha Ahmed, Fatimatu Abdy, Asalma Achej

Curatorial Advisor: Nina Zimmer

With the support of: University of Basel, Nordrhein-Westfälische Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Künste, Johann Raßhofer Schreinerei, Zumtobel Lighting, Typico, Swiss Arts Coundcil Pro Helvetia.

Photography: © Tchla Pachri, and Manuel Herz Architects

Exhibition: 30 ene - 27 nov 2016

The Western Sahara is a country located at the western edge of the African continent. Formerly a Spanish colonial territory, and since 1975 occupied by Morocco, it has been called the world’s last remaining colony. With the beginning of a guerrilla war against Morocco, most of the Western Saharan population - the Sahrawis - had to flee across the border into Algeria where it settled in refugee camps, today housing approximately 160.000 Sahrawis. Even though the Sahrawis do not have control over their own country, they proclaimed independence of the Western Sahara on February 27, 1976. Its sovereignty is recognized today by approximately 40 countries, though its status remains unresolved.

Having lived for 40 years in refugee camps in the border zone of south-western Algeria, the Sahrawi population has developed a unique set of urban and architectural tools, as well as design methodologies to deal with the condition of transience and liminality. The buildings address topics such as permanence and temporality, modesty and decoration, tradition and modernity. These terms are not understood as opposites, but they always co-exist simultaneously in the architecture of the camps.

-

Instead of seeing the Sahrawi camps as pure spaces of exception, or as the spatialized state of emergency, we need to acknowledge the everyday urban activities that play out in the camps, and how they are agents in the production of space. Spaces of everyday life show how the camp is used as a field of social, cultural, economical and political exchange, thus giving the camps an urban quality. It recognizes the importance of ‘normality’ in an abnormal condition.

Rabouni, the first camp that was established in 1976, was eventually transformed into the de-facto capital of the refugee nation. In this camp we find all the institutions that normally exist also in any other national capital: The parliament, several ministries, a national archive, a national museum and many additional national institutions. The settlement is a direct result of the semi-sovereignty that was granted to the refugees by Algeria. The Sahrawi refugees are in charge of their own lives and are not governed by other authorities. Rabouni reflects this autonomy. It is a physical manifestation of the camp and its architecture as a device for nation-building, and as a political project. The Sahrawis have thus developed a novel understanding of what role a refugee camp can play. They have proactively used the refugee camps as an opportunity to prefigure their nation, and as tools for social emancipation.

This contribution represents the first time ever, that a nation in exile is represented with a pavilion at the Biennale Architettura di Venezia. It also aims at using the - at times contested - concept of the ‘National Pavilion’ as an instrument to bring the Western Sahara on eye level with the other nations represented at the Biennale, while also allowing for novel ideas for the nation state to enter the debate.

At a time, when the topic of refugees is dominating the news of today’s media, and the Western world is at odds how to deal with this dynamics, a contribution that brings in a new perspective of refugees as self-determining and sovereign individuals through architecture, is more than crucial and shows the relevance of our discipline of architecture and urbanism.

The conflict

Formerly a Spanish colony, the Spanish dictator Franco drafted an agreement in 1975 that led to the occupation of the Western Sahara by Morocco and Mauritania, after a Spanish retreat. A guerrilla war ensued between the occupying forces and the Sahrawis, driving the Sahrawi population into refuge across the border in Algeria, near the Algerian city of Tindouf. Even though Mauritania withdrew from the conflict in 1979, Morocco occupied more and more of the Western Sahara territory by building a succession of walls and mined fortification lines, cutting through the desert country. These so called 'berms' - several thousand kilometers long - divide the country into a occupied zone, and the so-called Liberated Territories. Since 1991 a ceasefire has stopped the fighting, though a referendum on the future of the country has been consistently delayed by Morocco. The Moroccan occupied area holds one of the largest phosphate deposits on this planet and gives access to rich fishing grounds off the coast in the Atlantic Ocean.